Why do female astronauts take birth control pills before flying to space? What is it meant to prevent?

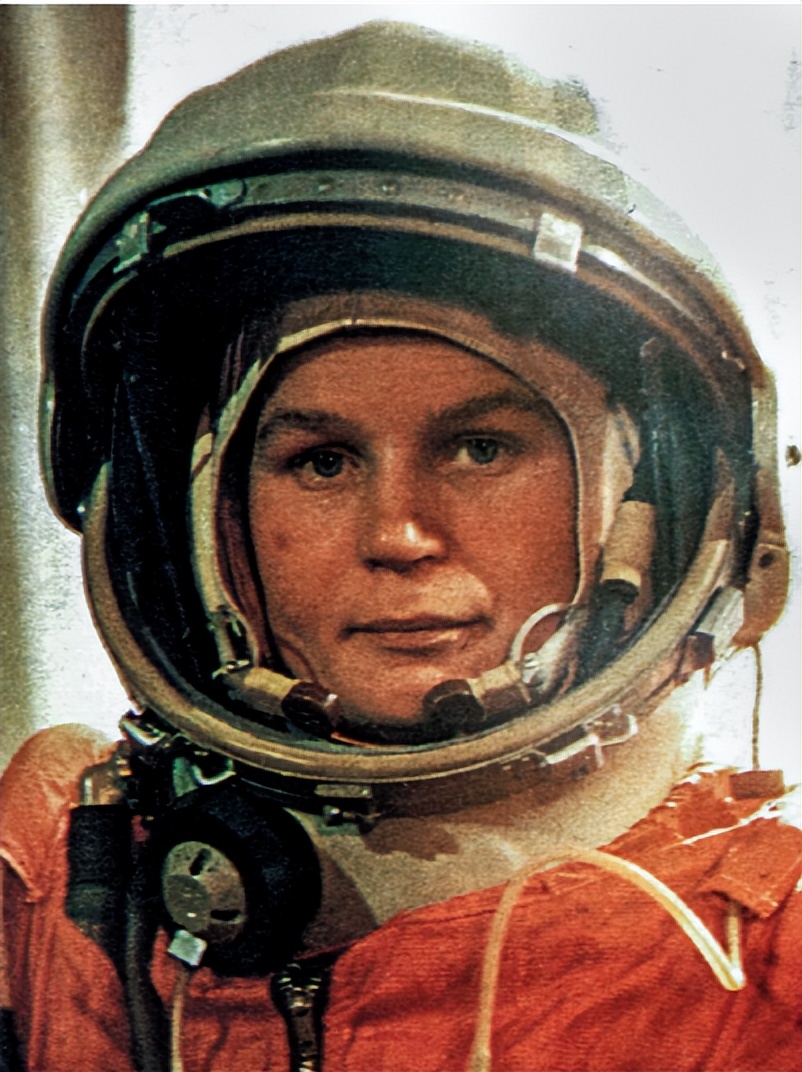

In 1963, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova successfully entered space, becoming the first woman in human history to travel to space.

Behind her success lay a detail unknown at the time: she took birth control pills before launch.

This set a precedent for physiological management of women in spaceflight, but also raised a question—why do female astronauts take birth control pills before flying to space?

The images and descriptions in this article are sourced from the internet, aiming to promote positive energy and avoiding any misleading content. If any copyright or infringement issues are involved, please contact us immediately, and we will delete the content promptly. The information is reliable, though some details may be fictionalized for enhanced readability and is for reference only. Please read with a rational mindset.

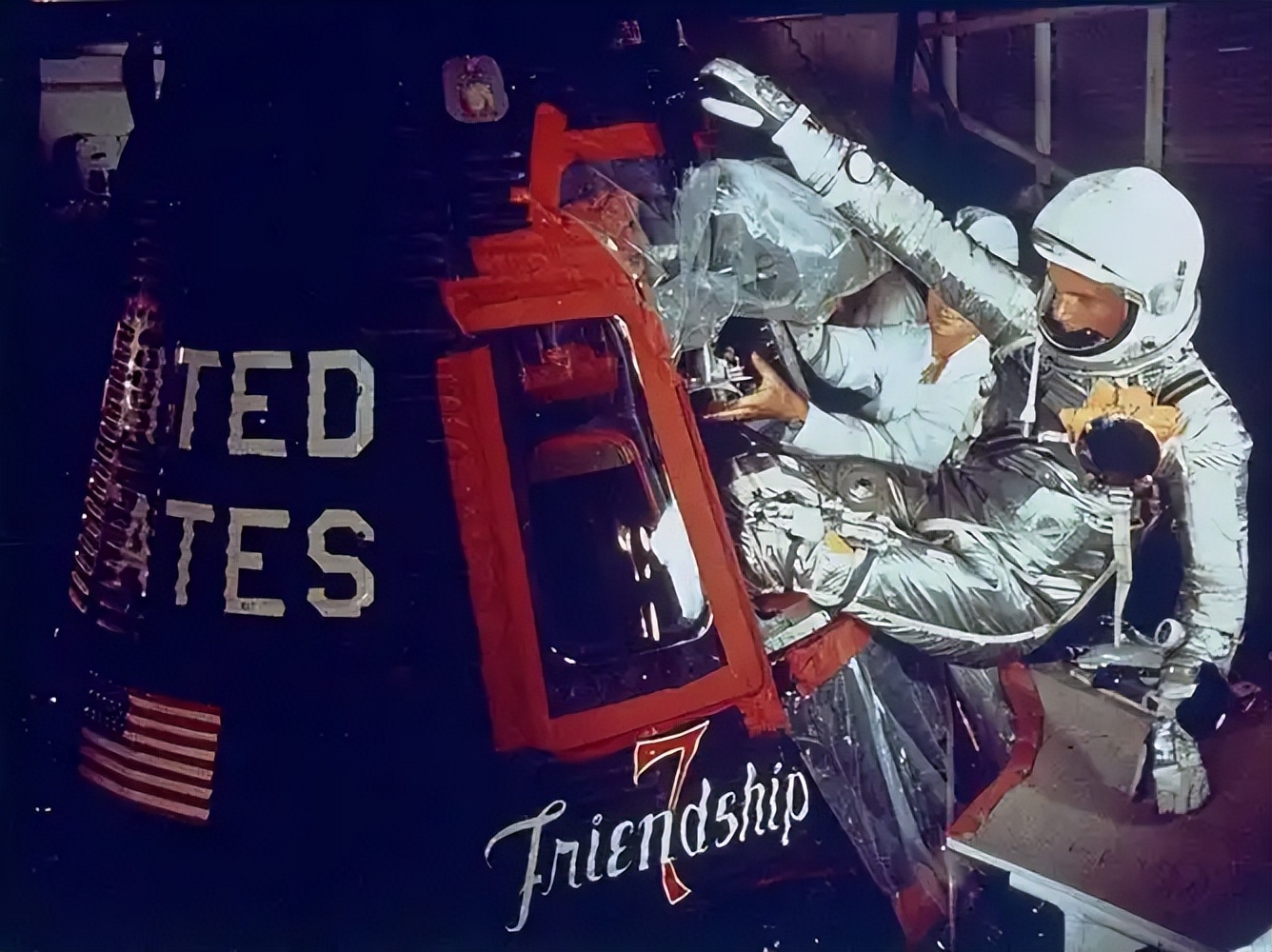

In the 1960s, NASA's Mercury program made a bold attempt—selecting astronaut candidates from female pilots.

After rigorous screening, 13 women stood out. Whether it was physical tests, flying skills, or psychological qualities, they were no less impressive than the male candidates.

Just as they were about to fulfill their dream of space travel, they were stuck by a surreal problem—how to handle menstrual cycles in space?

You see, the space environment is vastly different from Earth. Beyond microgravity and high radiation, the spacecraft is also extremely cramped, all of which pose challenges to the human body.

Just think about microgravity—the human circulatory system and endocrine system change in there, and for women, their menstrual cycle also becomes troublesome.

In fact, as early as the beginning of space exploration, scientists in ground-based simulation experiments discovered a troublesome situation: On Earth, women's menstrual blood discharge is smoothly carried out by gravity, but in a weightless environment, menstrual blood won't flow downward and may even flow backward into the abdominal cavity.

This is no small matter—it can easily lead to infections, menstrual cramps, and in severe cases, it can even affect health.

At that time, it was generally believed that in microgravity, women's menstrual cycles were likely to have problems, and it might even be life-threatening. Some people were also worried that if menstrual blood were to float around in weightlessness, it could contaminate the equipment inside the spacecraft.

Amid these concerns and biases about women's ability to adapt to space, the head of the "Mercury Program" was left with no choice but to make a difficult decision—cancel the flight qualifications of the 13 female candidates and entrust the entire space mission entirely to male astronauts.

On June 16, 1963, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova soared into space, directly shattering the ingrained belief that "women cannot go into space."

What everyone was most curious about was how to handle the "menstrual period" of female astronauts in the special space environment

The Soviet answer was particularly straightforward—Tereshkova took birth control pills before her flight to space, simply ensuring her menstruation "missed" during the mission, simple and efficient.

This move has frustrated the U.S. as they watched the Soviet Union take the lead in the field of female astronauts, prompting the U.S. to quickly recognize the role of women in space exploration.

However, the Americans had no intention of copying the Soviet method and felt they needed a more "decent" solution. So, in the 1970s, NASA spent a lot of money developing "space diapers."

It is said that this diaper used the most advanced water-absorbing materials and leak-proof technology at the time, specifically designed to address women's menstrual issues in space.

But ideals are full, while reality is quite stark.

This "space diaper" exposed many problems right after use: it was particularly troublesome to wear, bulky, and not lightweight. After all, spacecraft have extremely strict weight control, and this diaper instantly became a significant burden.

In contrast, the Soviet Union seemed much more pragmatic, continuing to use birth control pills to delay menstrual periods, allowing more female astronauts to successfully enter space for work.

In fact, the use of birth control pills by female astronauts in space missions has a scientific mechanism of action.

The commonly mentioned combined oral contraceptive pill primarily consists of estrogen and progestogen.

Female astronauts need only to start taking it regularly a few weeks in advance to temporarily put their ovaries "on hold" and prevent ovulation. The endometrium will also not thicken as usual to prepare for fertilization, and thus menstruation naturally ceases, reducing many inconveniences in space.

However, taking medication also comes with some concerns.

The risk of blood clots may increase with the use of birth control pills. In space, radiation levels are higher than on Earth, and astronauts spend most of their time in a sedentary or fixed posture. These two factors combined can further elevate the risk of blood clots.

Additionally, the weightlessness of space itself causes astronauts to lose bone density, and the hormone components in birth control pills may further exacerbate this issue, not being very friendly to bone health.

Fortunately, for these challenges, space agencies around the world have long thought up solutions.

Astronaut doctors will "tailor-made" plans for each female astronaut, selecting the most suitable drug types based on their physical condition, and will accurately adjust dosages to minimize risks as much as possible.

During the mission, the ground medical team will monitor the female astronauts' various physical indicators, such as blood pressure, blood clotting function, bone density, etc., 24 hours a day without interruption. Once abnormalities are detected, they can be addressed promptly.

Moreover, astronauts are scheduled for two hours of "resistance training" daily, such as deep squats and deadlifts on special equipment, to help maintain muscle strength and bone health. Additionally, they are specifically provided with calcium supplements to further protect their bones.

Moreover, later studies showed that the microgravity environment in space has no significant effect on menstruation; it's exactly the same as on Earth.

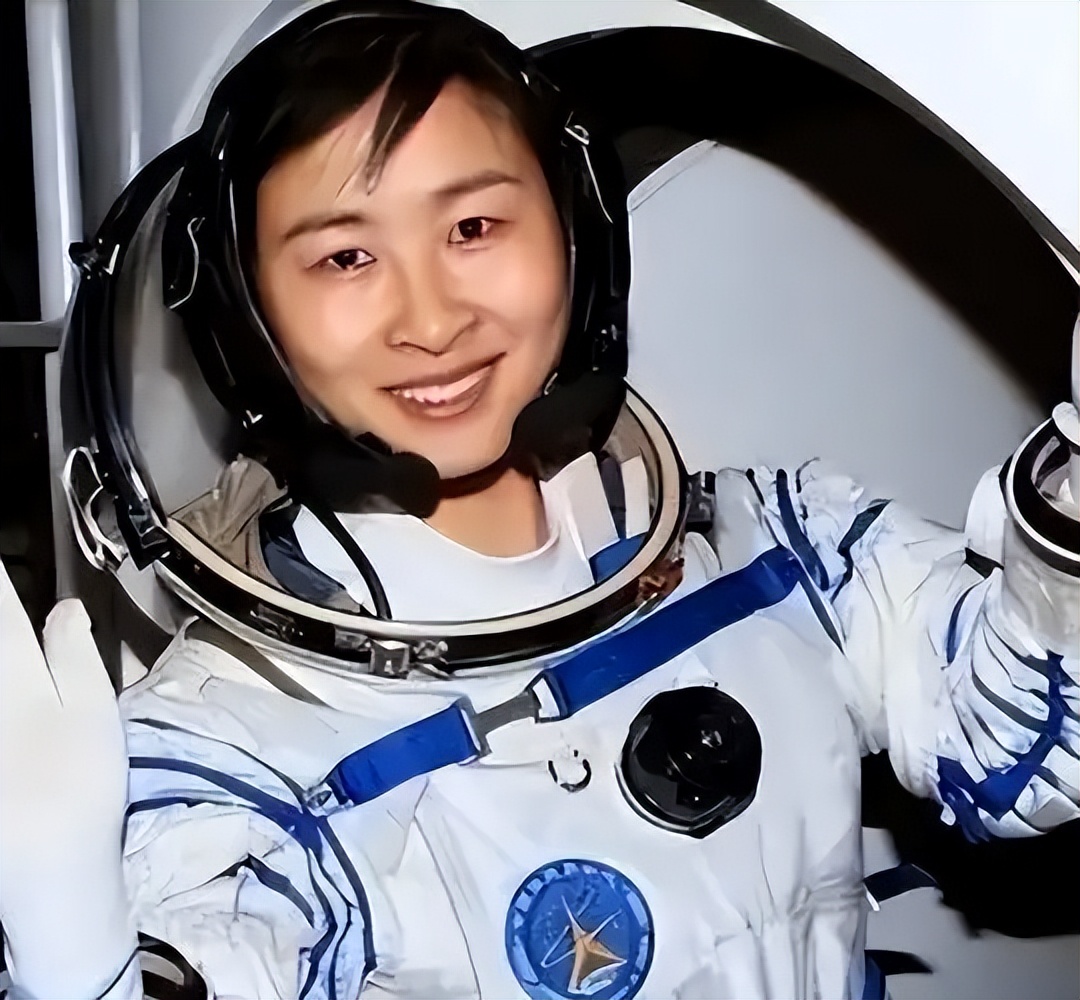

Now, whether it's space agencies in the United States or Europe, or our Chinese space team, they have all adopted this method of managing the menstrual cycle as the "standard procedure" for female astronauts to perform their missions.

If it's a short-term mission, such as only a few days to a few weeks, taking medication to delay the menstrual cycle is the simplest and most effective method. But if it's a long-term 驻站任务 lasting several months, other auxiliary solutions would be considered.

Some female astronauts use highly absorbent adult diapers or special sanitary pads, but this method requires special attention to hygiene, as it may increase the risk of infection.

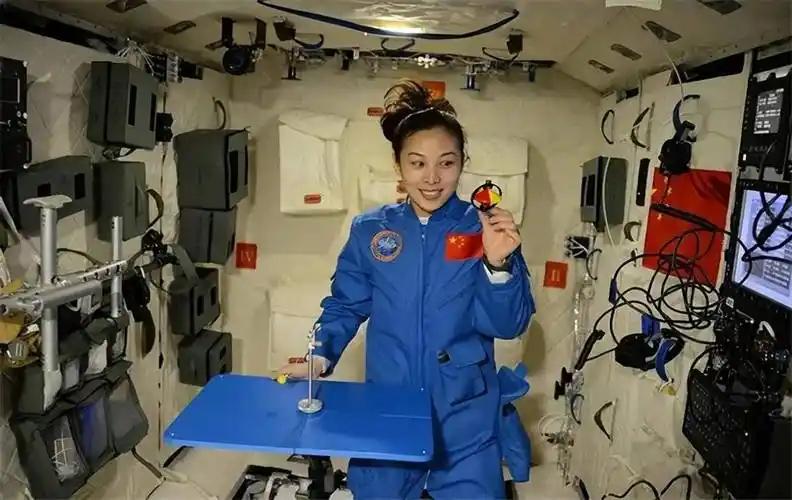

In our Chinese space station, there are dedicated living areas specifically designed for female astronauts, equipped with hygiene facilities that cater to female physiological needs, such as specially designed toilets, cleaning supplies, and more, providing more humanized living support.

Moreover, China's space medicine experts have not stopped their research efforts, continuously exploring safer and more convenient menstrual cycle regulation techniques, hoping to reduce reliance on contraceptive drugs, allowing female astronauts to perform tasks more comfortably and securely in space.

Currently, over 65 female astronauts have successfully entered space, leaving their mark in the cosmos with extraordinary courage and wisdom, and writing a new chapter in the history of human space exploration.

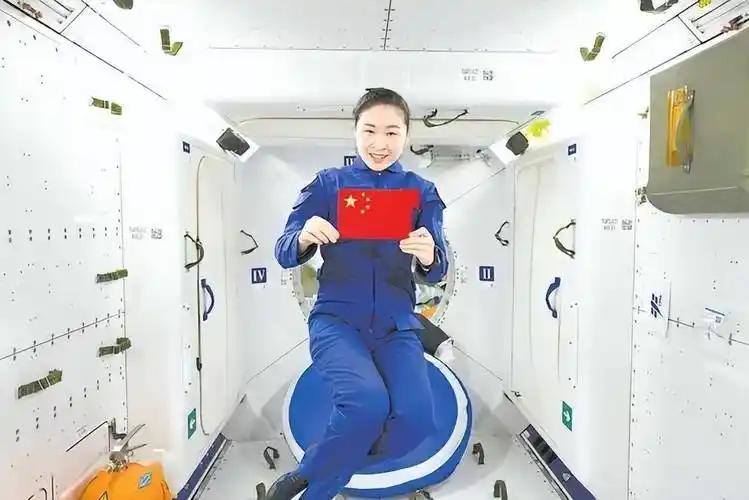

From the world's first female astronaut Tereshkova to outstanding female astronauts like Wang Haozhe in China, female space workers have steadily proven their capabilities, making space no longer a "special event" for men.

With the continuous development of space medicine, female astronauts are no longer passively adapting to the environment in space but can actively control their bodies, better engaging in space exploration endeavors.