A top-tier seller's account: E-commerce taxes will be investigated retroactively for two years; failure to pay could lead to imprisonment.

Since the deadline for submitting e-commerce tax data on October 27, a tax compliance storm sweeping the e-commerce industry has not subsided as many had predicted, but has instead intensified.

With platform data being fully integrated and tax supervision being tightened, many e-commerce sellers who once relied on "zero declaration" and "no tax declaration" to grow wildly are now facing a severe test of their survival.

A seller named Qiang (pseudonym) on the Pinduoduo platform, whose annual sales are nearly 200 million yuan, is a witness to this storm.

He recently revealed to Paida that because he failed to submit tax-related data on time, the tax authorities came to his door to conduct an audit after failing to contact him multiple times. They retrieved his actual sales data for the past two years and ultimately determined that he needed to pay more than 7 million yuan in back taxes.

Ah-Qiang frankly admitted that almost all the profits he had worked so hard to earn over the past few years had been "gone back," and his shop was in an unprecedented predicament.

What frustrated him even more was that with tax compliance becoming mandatory, the low-price strategy he relied on for survival became unsustainable. To cover the suddenly rising tax costs, he had to gradually increase the price of his products from 3.9 yuan to 6.9 yuan, causing monthly sales to plummet from millions of orders to 300,000 orders, a drop of more than 70%.

At the same time, the simultaneous increase in express delivery fees further squeezed the remaining profit margins, putting him in a dilemma of "raising prices is suicidal, not raising prices is waiting to die."

A-Qiang's experience is not an isolated case. With the implementation of e-commerce tax policies and the normalization of platform data reporting, those "unorthodox" business practices that used to operate in a gray area are now being brought under regulatory scrutiny one by one.

For many white-label merchants like him who grew up during the platform's boom period, this is not only a financial "make-up class," but also a reconstruction of business logic—survival no longer depends solely on low prices and traffic, but also on compliance, efficiency, and endurance.

Tax evasion ordeal: Tax officials came to collect payment, uncovering over 7 million yuan owed over two years.

“I was hoping to get away with it, so I kept putting off submitting the data. At that time, my business friends had already started receiving tax notices, but I always thought I could get away with it,” A-Qiang confessed to Paida. However, you can’t hide forever. Because he failed to submit the tax data before the October 27 deadline, in early November, after several unsuccessful attempts to contact him, the tax authorities came directly to his company.

Once they arrived at the shop, the problems could no longer be hidden. According to regulations, the tax authorities generally only check the data for the most recent quarter, but because A-Qiang's shop had a large turnover, it attracted the attention of the tax officials, and the scope of the audit was expanded to include transaction records from the past two years.

“All the data was obtained directly from the Pinduoduo platform by the tax bureau. After deducting the returned goods, the calculation was based on the actual sales amount.” A-Qiang’s tone was helpless. “What’s more troublesome is that if there are any fake orders, they will also be included in the tax base and cannot be deducted. Fortunately, I have not done much fake ordering in recent years, otherwise I would have to pay even more.”

Having consistently filed "zero tax returns" for the past few years, Ah Qiang was ultimately found to owe more than 7 million yuan in taxes when faced with the sudden revelation of his hundreds of millions of yuan in sales revenue. Despite his best efforts to find input invoices for tax deduction and his attempts to ask people to help him, he was still determined to have to pay more than 7 million yuan in back taxes.

The tax authorities made it clear to him that there was no room for leniency regarding the retroactive investigation; it was a policy red line. "They even said that if I didn't pay, I might even face criminal charges (jail) , and their tone really scared me. Fortunately, I had an acquaintance who helped coordinate, and the local regulatory environment was somewhat flexible, so the matter was eventually resolved—the money couldn't be avoided; I still had to pay it. From now on, I can only follow the compliant route." Speaking of this experience, A-Qiang still feels lingering fear.

It's worth noting that this audit only covers data from before the second quarter of last year. A-Qiang has yet to complete his tax return for the third quarter of this year. "The shortfall in input invoices is too large; the accounts simply don't balance. I can only delay it until the annual tax settlement in May next year. During this period, I have to do everything I can to find invoices and try to deduct as much tax as possible; otherwise, no one can withstand this tax rate. I definitely can't escape the late payment fees, and I'll have to accept the penalties I'm owed."

He revealed that in the past, small and medium-sized e-commerce sellers generally did not pay taxes, which was almost an industry "open secret". "In the early days, there was no concept of e-commerce tax. Almost everyone around us who did Pinduoduo declared zero, and no one checked. It wasn't until the policy came out that the platform started to synchronize data with the tax bureau. Before, if the platform didn't report, the tax authorities had no idea how much money you actually made."

Ah Qiang said with a wry smile, "In the past, the tax authorities would occasionally come by and ask how many people worked in the store and how much they sold. I would just say two or three hundred thousand a month, and they wouldn't even give me a second glance. But now it's different. Everything has to be compliant. For people like us who come from 'unconventional' backgrounds, it's really tough to be completely compliant without going through a lot of trouble."

Cost Blow: Annual Profit Lost by 4 Million After Compliance

The pain of paying back taxes hadn't subsided, and how to survive under the new regulations became the next major challenge Ah Qiang had to face. With compliance becoming the only way out, he quickly sought help from tax experts, attempting to find the optimal solution within the legal framework.

"I had a professional calculate it, and now we have to use 4% of the turnover to pay taxes. This is the best solution after trying every possible method," said A-Qiang. Behind this "best solution" is a complex multi-entity operating strategy that operates in a gray area.

First, it is necessary to establish a "company matrix" to maintain the status of a small-scale taxpayer.

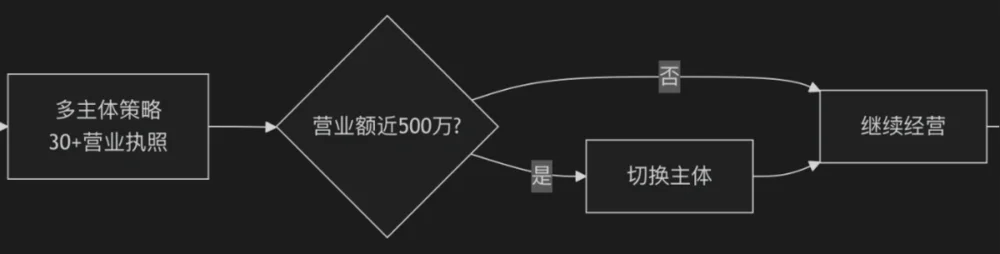

A-Qiang's core strategy involved registering over 30 business entities across China, including Hong Kong. "The idea is simple: 'divide and conquer'," he explained. "When one entity's annual turnover approaches the 5 million yuan threshold for small-scale taxpayers, it's discontinued, and another entity is switched to continue operating. Hong Kong and other places offer tax incentives, allowing for even higher thresholds."

To avoid associated risks, the legal representatives of these entities must be people who have absolutely no connection to A-Qiang. "We absolutely cannot use our own or relatives' ID cards; it's easy to get caught if we do. Finding these people and completing the formalities are all handled by the cooperating financial and tax companies."

A tax official once advised him at a dinner party: "Don't be too obvious, they usually won't investigate too deeply. As long as each entity pays its due taxes, just don't go too far." But A-Qiang knew in his heart that this was not a foolproof plan, "If the higher-ups really want to investigate, they will definitely find out."

Secondly, tax planning is necessary to keep the overall tax burden below 4%.

By employing a multi-entity strategy, A-Qiang maintained the VAT rate at 1%. Simultaneously, by compliantly obtaining input invoices and properly listing costs such as promotion expenses and employee salaries, he kept his income tax below 3% of turnover. Combined, these measures achieved his goal of a "comprehensive tax burden of approximately 4%".

"Income tax is flexible; the key is cost invoices. For example, platform promotion expenses can be invoiced, and employee salaries can also be treated as costs. By piecing together various costs, we can finally reduce the tax burden," A-Qiang admitted.

In addition, the supply chain should bear some of the pressure, forcing factories to issue invoices, but costs cannot be increased.

The real challenge of this solution lies in the supply chain. As a white-label retailer, A-Qiang's product profit margins are extremely thin. If the factory raises prices due to invoicing requirements, the upstream suppliers will be unable to bear the losses.

“I can only put pressure on the factory,” A-Qiang said bluntly. “I told them that they must help me get this ticket sorted out. If they can’t, the project will go bankrupt and no one will be able to do anything. We are all in the same boat, and we can’t rely on me to find a solution all by myself.”

He wasn't clear on the specific methods the factory used to resolve the invoice issue, but the result was that the cost price didn't increase. This meant that he had to absorb almost the entire 4% tax burden himself.

"This is the best solution we can think of by mobilizing all our resources." A-Qiang did the math: with annual sales exceeding 100 million yuan, more than 4 million yuan has to be paid in taxes every year. "This 4 million yuan was the real profit we used to make. The price of compliance is that we earn the equivalent of one house a year less."

The Battle for Survival: Sales Plummet by 70%, Price Hikes for Survival and the Dilemma of White Label Brands

Before the tax costs could be fully absorbed, a survival crisis loomed. To cover the tax costs, which amounted to 4% of turnover, A-Qiang was forced to raise product prices while drastically reducing the promotion budget. However, the market gave the most direct feedback: "Sales plummeted by 70%, with monthly sales dropping from 1 million orders to 300,000 orders, but we had no choice but to tough it out."

Even more serious is that cost pressures don't come from a single source. Just as the e-commerce tax storm was sweeping through, express delivery fees also experienced a surge. "Previously, a single express delivery cost only 0.9 to 1.1 yuan, but starting in November, it generally rose to 1.9 to 2.2 yuan," lamented A-Qiang. "With express delivery and taxes hitting us from both ends, the operations side has to be completely restructured, otherwise every link we create will result in a loss."

For the low-priced general merchandise that A-Qiang sells, the meager profit margin simply cannot withstand these two heavy blows simultaneously. Products originally priced at 3.9 yuan per item with a gross profit margin of about 13% saw their profits wiped out instantly by the e-commerce tax and doubled shipping fees. Starting in October, he had to gradually raise the price to 6.9 yuan per item, which resulted in a precipitous drop in sales.

“Our business model has a very low gross profit margin, and we rely entirely on volume to support our total profit,” A-Qiang explained. “It’s incomparable to those high-priced products. Others sell something for tens of yuan, and adding one or two yuan in tax just means they earn a little less; for us, it’s a death sentence, and the whole project is about to go out of business.”

Faced with this predicament, A-Qiang didn't simply raise prices across the board. Instead, he conducted a meticulous price test. "I can't just raise it to 6.9 yuan all at once, that would be 'dead'," he shared his strategy. "I tested it at the same time with prices of 4.9 yuan, 5.9 yuan, 6.9 yuan, and 7.9 yuan, with 10 links for each price, promoting them together to see which price range had the best data feedback and could still maintain a gross profit margin of about 10%.

Ultimately, 6.9 yuan was proven to be the "lowest price" and "lowest gross profit margin" that could achieve survival under the current cost structure. "Although the scale has shrunk a lot after the price increase, at least this project can survive."

When asked why they consistently maintain such low prices, A-Qiang revealed the common predicament of white-label merchants. "Our past strategy was very brutal: we would target big brands, and when they released a new model, we would copy it. If they sold it for 9.9 yuan, we would sell the exact same product for 3.9 yuan." This extreme price war is the only survival rule for white-label merchants who lack brand power and traffic support.

“We couldn’t even sell it for 6.9 yuan and not many people bought it. We could only get orders by slashing the price to an unbelievable level.” A-Qiang also tried to break through by cooperating with factories to develop mid-to-high-end products and using better materials to compete with branded products, but it ended up losing 100,000 yuan. “We had to stop after a month. How can a white-label company like us compete with brands in the high-end market? Just saying that the quality is good is not enough for consumers to believe.”

He further pointed out the deep-seated obstacles to the transformation of white-label brands: "Our stores generally have very poor DSR (Dynamic Seller Rating) , which the platform does not recognize, so it does not provide resources such as black labels. To build a brand, you need a long-term and large-scale investment. In the current environment, who dares to easily throw money at it?"

The supply chain advantages accumulated over many years in the department store category have now become A-Qiang's last line of defense. Unable to easily switch tracks, he can only do his best on the operations side in this battle for survival, looking for every bit of room to maneuver.

The darkest hour: Survival is victory; whoever can endure it wins.

As A-Qiang struggled to adjust amidst the quagmire of rising prices and plummeting sales, he noticed a perplexing phenomenon: most of his competitors maintained their original prices, and sales remained brisk as usual. "Their prices haven't changed, and they're still selling like hotcakes."

Ah Qiang was full of doubts about this. "Either the tax authorities haven't investigated them yet, or they have other ways. I can only do it as it comes and see. When it's their turn to be investigated, they will definitely have to raise their prices too."

The precipitous drop in performance undoubtedly hit the team's morale hard. "The whole company atmosphere was very low. After all, the data wasn't good, and everyone was uncertain." Despite this, A-Qiang made a decision: no layoffs. "I'll keep the team size the same, but the strategy must be adjusted. In the past, we pursued a gross profit margin of 12 to 13 percent. Now, let's be more realistic and aim to stabilize the gross profit margin at around 10 percent. Let's all work together to find ways to achieve this new goal."

In his view, maintaining team stability is the foundation for surviving this difficult period. "People are the most important asset. Although it's tough now, as long as the team stays together, we can react quickly when the market recovers."

Regarding the long-term impact of the e-commerce tax, A-Qiang expressed unexpected optimism. "It will definitely be painful in the short term, but in the long run, survival will not be a problem." He judged that this was not just his predicament, but a common challenge that the entire low-price white-label industry would soon face.

“If all merchants like us on the platform eventually face the same compliance costs, then everyone will be forced into the same price range. At that time, my price will no longer be a disadvantage, and the market size will naturally recover.”

He defines the current period as "the darkest hour for e-commerce," a necessary growing pain as the industry moves towards standardization. "Only when all players regard e-commerce taxes as fixed costs will a new market order be established, and only then can white-label merchants like us find a stable space to survive again."

However, rebuilding order takes time. A-Qiang predicts that this "darkness before dawn" will last at least six months to a year. "Now it's a competition to see who can hold out the longest and who can survive to the end. Whoever perseveres will be the winner."

He didn't have a grand transformation plan or a disruptive business model. His only strategy was to "endure"—maintaining a minimum level of survival within a compliant framework through extreme cost control and operational optimization, and patiently waiting for the industry landscape to be reshaped and restructured.

In this transitional period filled with uncertainty, simply surviving is the greatest victory.