Japanese drugstores are finding it harder to profit from Chinese consumers.

The depreciation of the yen, the widespread use of WeChat Pay and Alipay, the opening of duty-free counters, and the increase in Chinese-speaking shop assistants have made drugstores such as Matsumoto Kiyoshi and Daikoku naturally popular shopping destinations for Chinese tourists.

However, when I recently took a friend from China to a drugstore, she didn't buy much and kept saying: "I'll buy it on Taobao later and check the reviews before deciding."

Did reason prevail, or has the appeal of drugstores declined?

In my opinion, Japanese drugstores will find it difficult to continue profiting from waves of Chinese consumers, or at least it will be unsustainable.

To be precise, those colorful, readily available cosmetics, skincare products, health supplements, medicines, and snacks, while still appealing, have lost their appeal. The era of scarcity and exploitation is over.

one

Is the significance of a drugstore simply "medicine" + "cosmetics"?

We'll discuss JACDS' (Japan Chain Drugstore Association) definition of the drugstore concept later. However, for Chinese people, the name "drugstore" represents this specific business model.

Medicine? Actually, tourists from mainland China didn't have any particular colds.

Although Kobayashi Pharmaceutical's fever-reducing patches and EVE painkillers are well-known best-selling products, we are not their primary customer base. According to the Japan Tourism Agency's "Consumption Trends of Foreign Visitors to Japan," the top two regions for purchasing Japanese medicines are Taiwan and Hong Kong, especially Taiwan, where the average purchase price is 22,492 yen, equivalent to more than 1,000 yuan.

They went to the drugstore to "stock up".

What about "makeup"? According to official Japanese statistics, the largest consumer of cosmetics is mainland China.

The "Consumption Trends of Foreign Visitors to Japan - Annual Report 2024" shows that the proportion of mainland Chinese tourists purchasing cosmetics is the highest (54%) , far higher than that of Hong Kong (38%) , Taiwan (33%) , South Korea (21%) , and the United States (17%) .

However, this doesn't mean that drugstores are thriving. Most well-known cosmetic brands can only be purchased at department store counters, while people go directly to drugstores to buy unknown or over-the-counter cosmetics.

(Canmake)

(KissMe)

In my opinion, over-the-counter cosmetics will only become increasingly less appealing to Chinese consumers. Aside from brands like Kate, Curel, and My Beauty Plus that have entered the Chinese market, and popular products like Canmake (the Japanese version of Perfect Diary) and KissMe eyeliner, most Japanese drugstore cosmetics haven't achieved global distribution. Given that the names, functions, and even brand names are in Japanese—which even foreigners living in Japan might not understand—will tourists really buy them in large quantities?

two

In fact, discussing "medicine" or "cosmetics" alone cannot address the biggest problem that drugstores have in attracting Chinese consumers: Japanese products in drugstores have been completely replaced in China, or rather, they have never become mainstream or entered daily life.

Think back to the peak period of Chinese tourism to Japan from 2016 to 2019, how many people gave Japanese cosmetics as a presentable souvenir?

There were three driving forces behind the buying spree back then:

Trust in and the myth of Japanese quality (efficacy + hygiene + packaging)

Price difference (exchange rate + tax exemption)

Domestic shortages or not yet introduced

However, firstly, there is no longer a shortage of goods in China. Currently, brands such as Kao, Kobayashi Pharmaceutical, Kisme, Ohta's Isan, Anessa, Canmake, and Kate all have flagship stores on Tmall, and even Matsumoto Kiyoshi, the leading drugstore chain, has its own flagship store in China.

Instead of incurring extra travel costs, it's better to buy domestically. Moreover, depending on the specific type and specifications, exchange rate, shipping costs, and promotional periods, buying in China might actually be cheaper. For example, the Kao Mesotherapy Steam Eye Mask I saw in a drugstore cost 1408 yen (approximately 64 RMB) for 12 pieces including tax, while the domestic price was 101 RMB for two boxes at the Mesotherapy flagship store and 229 RMB for four boxes on Tmall Global. The only drawback of cross-border e-commerce is that discounts are only available for bulk orders.

Secondly, is it really necessary to buy Japanese goods? Aren't established brands like Procter & Gamble and Unilever alternatives? Chinese domestic brands are so vibrant, and there are so many product varieties available today—aren't they appealing?

There's a joke online: when someone goes from frequently chatting with you to suddenly becoming silent, it's usually not because they've gotten busy, but because they've moved on to someone else. In other words, their desires have been fulfilled elsewhere. The same applies to the demand for consumer goods.

Since the rise of short video platforms, most of China's new wave of consumer brands have grown by leveraging traffic. Even small workshops can operate quickly and efficiently, focusing solely on marketing without worrying about anything else. After all, unlike Wahaha and Nongfu Spring in the past, they no longer need to engage in fierce battles for market share or spend exorbitant amounts on advertising to survive. Nowadays, anyone can engage in low-cost marketing and make a small profit.

According to "Jumeili," in the Top 10 of the beauty category on Tmall's Double Eleven in 2024, the only Japanese brand was SK-II, which ranked fifth from 2017 to 2019, but has now fallen to eighth. The overall skincare ranking released by Douyin e-commerce shows that leading Japanese beauty brands CPB and Shiseido are only ranked 18th and 20th respectively. On the Kuaishou e-commerce platform, no Japanese brands made it into the top 20. The real top 20 consists of either major brands like L'Oréal, Lancôme, and Estée Lauder, or domestic brands like Pechoin, Mao Geping, HBN, Marubi, and Guyu.

Another advantage that Japanese products once had was their wide variety and specifications. Ten years ago, I saw an entire wall of toothpaste in a drugstore, and it felt like a whole new world had opened up for me. In Japan, there are at least 48 types of girls you might like, like AKB48, and you can find 48 different kinds of toothpaste for that matter.

But today, the explosion of creativity has shifted from the supply side to China.

As I manage my company's WeChat mini-program, I've observed new product categories that are gaining popularity on Xiaohongshu, such as shampoo bars and Liubao tea. The smaller the brand, the more unique and flexible it is in starting with rare product categories, revitalizing itself through various means such as concepts, product categories, marketing, and communication.

Moreover, the rise of many Chinese brands lies in learning from the West to surpass them. Brands like Florasis, Poya, HBN, Runbaiyan, and Ximuyuan, which saw massive sales during Singles' Day, all bear the mark of Japanese design and concepts. I used to think Japanese drugstore cosmetics were like the future; now I think they're like the past.

Actually, there was another very important turning point: the mask incident, which made us cross Japanese drugstore brands off our daily must-have list.

In 2019, Tmall's Singles' Day sales reached 268.4 billion yuan, and in 2020 and 2021, they skyrocketed to 498.2 billion yuan and 540.3 billion yuan, respectively. While Japanese goods are good, people are stuck in China and can't buy them. Does that mean demand has been suppressed? In the past, Chinese people would buy fine horses in the east market and saddles in the west market, buy eye drops in Japan and plasters in Southeast Asia. Now? Using domestic products is just as good. Even the wildly popular EVE painkiller, isn't its main ingredient ibuprofen?

If things are no longer "everyday," they return to the realm of experience and novelty. While Japanese goods may not collapse, their sustainability is questionable.

three

Drugstores are representative of offline retail in Japan. It is said that Japan's retail industry is exceptionally developed. Who are the representative companies? Let's compare drugstores, convenience stores, supermarkets, 100-yen stores, and Don Quijote.

In my observation, articles about "Japan's past" (such as the lost 30 years) seem to garner more traffic than those about "Japan's present." However, I believe this shouldn't be the case. Living in Japan, I tend to focus on long-term business observation. Only by viewing Japanese business with a developmental perspective can we see how they handle crises and opportunities.

(Drug-store)

The concept of a " drug store " originated around the 1980s. At that time, Japanese pharmacies began to transform, introducing health foods (supplements) , cosmetics, and other products. According to JACDS (Japan Association of Chain Drugstores) , drugstores sell:

Medicinal products (drugs) and quasi-drugs (quasi-drugs)

Cosmetics (including basic products, makeup, and brands for sensitive skin, etc.)

Health foods (health supplements, foods with functional claims)

Daily necessities (baby care products, tissues, cleaning agents, etc.)

Baby products

Oral care products

Food, and some stores have even started selling fresh food.

Not every drugstore sells prescription drugs; only those with a "dispensing window" can. Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs can be purchased at drugstores. In Japan, OTC drugs are divided into three categories, with higher-risk drugs subject to stricter regulations. Sometimes, simply buying the medication isn't enough; the pharmacist at the store will come and offer some advice.

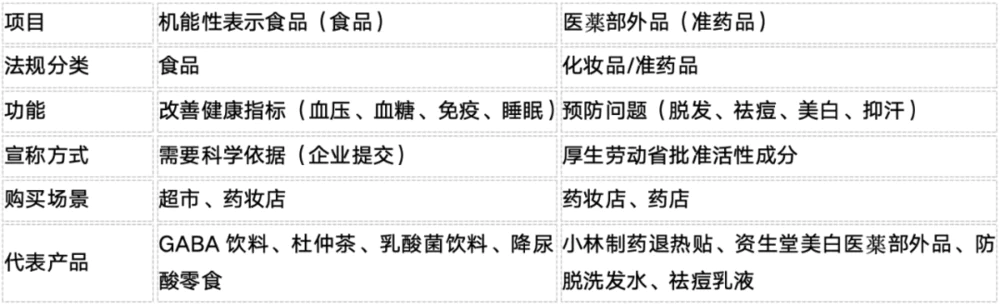

Please note that there is no such category as "drugstore cosmetics" in Japan; this is a concept specific to the Chinese-speaking world. Drugstores sell three categories of products: pharmaceuticals , quasi-pharmaceuticals (quasi-drugs) , and cosmetics. Cosmetics generally do not contain pharmaceuticals, but quasi-pharmaceuticals may contain approved functional ingredients, so consumers may experience a mixed feeling of something that is neither purely pharmaceutical nor purely medicinal.

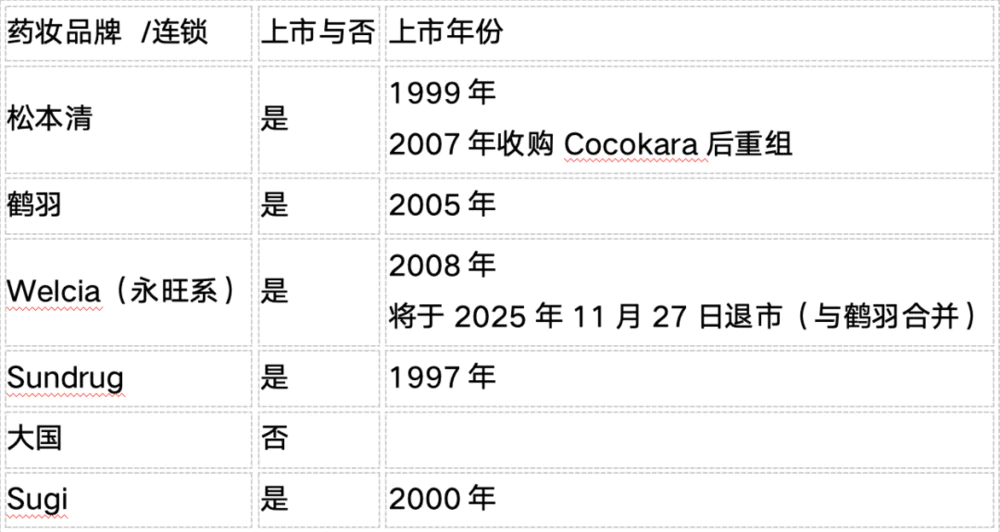

In the past two years, there has been a lot of news in the Japanese drugstore industry, and it's all been major news.

(JACDS)

In 2024, total sales of Japanese drugstores surpassed 10 trillion yen for the first time, achieving the mid-term target set by the Japan Association of Drugstore Chains (JACDS) a year ahead of schedule. With 957 and 682 new drugstores opened in 2023 and 2024 respectively, it's clear that expansion has reached its peak.

On April 30, 2025, the Japan Fair Trade Commission approved the business integration plan of Welcia Holdings and Tsuruha Holdings. With Welcia under the famous Aeon Group, both brands are now under Aeon's umbrella, directly surpassing the most well-known Matsumoto Kiyoshi.

Drugstores also have different positioning.

Matsumoto Kiyoshi is known for its stores in central and tourist areas, with strong marketing capabilities and high brand recognition. In 2021, it merged with Cocokara, which has a stronger network of stores in communities and suburbs, catering to the daily needs of local residents.

Heyu and Welcia are like family; Heyu focuses on opening stores in the region and places great emphasis on medical services, offering services such as online eligibility verification, electronic prescription systems, and electronic medical record integration. Welcia values "medical care + community," with 70% of its stores offering prescription drug (dispensing) services.

Daikoku is very attractive to tourists, and its stores are mainly located in tourist-heavy areas. It originated in Osaka, with the most branches in Osaka City and Hyogo Prefecture. Many of its staff speak foreign languages, and it also has duty-free counters.

Sundrug caters more to local residents and community consumers, offering reasonable prices and a wide variety of functional foods.

Sugi has a particularly strong membership system (high loyalty among members) , which is especially prominent in the Chubu region, such as Aichi Prefecture, where Nagoya is located.

The fact that various brands have joined forces to achieve sales of 10 trillion yen is by no means due to luck. Japanese drugstores have two faces: stores near tourist attractions, which select popular tourist items and souvenirs, and you can usually find one or two Chinese staff members there.

In areas slightly further from tourist attractions, drugstores have become more like small supermarkets, offering bread, frozen foods, and often at prices lower than supermarkets. Last weekend, I visited Matsumoto Kiyoshi first and then Seiyu Supermarket, but ended up buying chicken meatballs and frozen edamame at Matsumoto Kiyoshi, while only buying vegetables at Seiyu.

However, some drugstores have started selling boxed meals, such as Matsumoto Kiyoshi's food fortification stores.

Clearly, these non-touristy drugstores aren't targeting foreign tourists; they cater to locals and have an extremely detailed understanding of their needs. Japan's population structure is gradually changing. In cities like Tokyo, the number of neighborhoods is increasing, and residents want to buy all their daily necessities in one go. However, supermarkets are often far away, and convenience stores are too small and have limited stock. This is where drugstores shine again.

Besides food, prescription drugs and functional health supplements have also been significant drivers of growth for drugstores in recent years. Humanity is quickly expanding the scope of drugstore operations.

Four

The drugstore sells Japanese products. Let's chat briefly about how Japanese products became so popular.

In fact, they are taking an alternative route to go to sea.

As an island nation, Japan, apart from its strong industries like automobiles, didn't focus much on "going global" in its early years. Instead, it remained self-sufficient and self-sufficient. After World War II, Japan's automobile industry rose rapidly, and the oil crisis fueled international demand for fuel-efficient vehicles, allowing Japanese automakers to capitalize on this opportunity.

Besides automobiles, Japan also exported many other industries after the war: consumer electronics (Sony, Panasonic, etc.) , machinery and equipment, and precision instruments. However, the export of everyday consumer goods was not as systematic as that of automobiles.

The surge in popularity of Japanese goods is due to tourists buying them and taking them back to their home countries. The products' unique characteristics (packaging, effects, variety of sizes, and refinement) have generated significant traffic. Initially, it spread through private channels, gradually leading to keyword searches on social media. Personal shoppers also contributed to this growth, and now platforms like Xiaohongshu act as amplifiers, precisely amplifying their influence.

Therefore, Japanese goods are not exports, but they are better than exports.

In fact, many Japanese companies never planned to go global in the first place. The lack of English on their packaging created a significant barrier, making it difficult for foreigners to identify and choose their products. The fact that almost all J-POP songs have Japanese titles, while K-POP songs are almost entirely in English, illustrates this point.

While some suffer from floods and others from droughts, Japanese goods have unexpectedly flourished, forming a unique category and precisely targeting the needs/pseudo-needs of the Chinese people.

Enzymes → For those who want to lose weight but don't want to exercise or diet;

Barley grass juice → For people who don't like eating vegetables but want to supplement their dietary fiber;

Kobayashi fever-reducing patches → For mothers who can't find similar products in China;

Heated eye mask, deodorant → for those seeking mild health maintenance and a high quality of life;

Canmake → For students who enjoy selecting product categories and shades.

Kobayashi Pharmaceutical's fever-reducing patches, gastrointestinal medicines, and deodorant are all highly conceptual, with few alternatives. However, the Red Yeast Rice scandal broke out, revealing that this health product caused kidney damage in users, resulting in 119 deaths related to the product. Kobayashi Pharmaceutical suffered cumulative losses exceeding 475 million yuan.

This directly caused a major blow to all Japanese products:

Japanese cosmetics sold in drugstores emphasize functionality, but are they really effective?

These cheap health supplements, while unlikely to kill you, won't help you either. Yet now, someone has died from red yeast rice. Is there no bottom line?

EVE painkillers are effective, but they are banned in other countries. Why is that?

Many foods contain iron, folic acid, GABA, and other nutrients. Drinking yogurt can help you sleep, killing two birds with one stone. But is this advisable?

Some review accounts have specifically urged people to be cautious when buying Japanese drugstore cosmetics, because in other countries, medicine is medicine and cosmetics are cosmetics, and Japan allows too many ingredients to be added, which may be unsafe.

Here, my view is twofold: First, the term "cosmeceutical" is merely a Chinese concept and is not inherently wrong. However, Japanese products that resemble medicine but are not truly medicine should not be expected to meet high expectations. Second, China has over a thousand prohibited ingredients in pharmaceuticals, far exceeding Japan's 30-plus. This does not mean that Japan is more lenient or less safe, but rather that the two approaches are different.

China uses a "list of prohibited ingredients" approach, explicitly listing prohibited ingredients; Japan uses a method of proof by contradiction, employing a "positive list + prior approval system" (somewhat similar to the Japanese stem cell model we wrote about before) . Other ingredients must be proven safe before use, rather than being explicitly prohibited. In fact, the number of usable ingredients in Japan is actually even smaller.

For example, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare's "Cosmetic Standards" and "Specifications for Quercetin Raw Materials" require Japan to implement a positive list system for cosmetic additives: 8 types of preservatives, 30 types of ultraviolet absorbers, and 76 types of colorants; once a new functional ingredient is involved, toxicological data must be submitted and awaited approval from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the approval process is on an annual basis.

The unique aspect of the Japanese market lies in the Japanese people's fascination with "functional foods" and " quasi-pharmaceuticals ." Ultimately, this stems from the severe aging population and the Japanese government's urgent desire to "functionalize food" to alleviate its healthcare burden.

Functional foods do not require the same approval process as medicines and can be sold in large quantities in supermarkets and convenience stores.

GABA content can reduce stress and help with sleep;

Yogurt containing vitamins, iron, and folic acid is available everywhere;

Lactic acid bacteria can be easily added to beverages and cookies;

Oolong tea containing "fat absorption inhibitors" is twice as expensive as regular tea.

The Japanese are obsessed with "functional foods" and "quasi-drugs." So why did the quasi-drug category exist? Because in the 1960s, Japan believed that some substances had weak efficacy and couldn't be classified as medicine, but treating them entirely as cosmetics was also unsafe. Quasi-drugs were thus created, with even stricter requirements than for cosmetics.

Raw materials must be registered within the pharmaceutical regulatory system.

The active ingredient has a maximum permissible concentration.

Packaging and copywriting cannot be written carelessly (there will be penalties).

It has a clear purpose for consumers; there's no need to guess.

However, the efficacy of these products is far weaker than that of genuine OTC drugs. The companies' exaggerated claims about their functions create a mixed experience that resembles medicine but is not, which can easily lead to misunderstandings among consumers.

Japanese consumers consistently rank among the highest in loyalty to domestic brands among the surveyed countries. However, regardless of the circumstances, if the "safety" facade is breached, it would be catastrophic for cosmeceuticals. For us Chinese, there's even less reason to take that risk.

five

When shopping bags become lighter, the relationship between tourists and Japan becomes more authentic.

Who are the drugstore brands targeting? Mainland Chinese tourists visiting Japan for the first time are most likely to be the ones getting ripped off.

As someone born in the 1980s, I was also one of those "leeks" (a term for people who are easily taken advantage of) when I traveled to Japan more than ten years ago. I went into a drugstore and it was like a long-awaited rain after a drought.

Back in the day, influenced by K-pop and Running Man, young Chinese people flocked to South Korea to see the Nanta Show and shop at Lotte Duty Free. Why isn't South Korea as appealing as it is now? Seoul and Jeju Island are the only two options, indicating a lack of tourism resources.

Japan has enough tourism reserves to keep people coming back again and again, but I think this will actually make drugstore products less and less popular.

Those who have visited Japan multiple times are no longer satisfied with simple checklists and are starting to explore less-traveled attractions. The more they crave in-depth travel, the less easily they're misled by unknown searches, and the more they enjoy buying limited-edition and local specialties. According to the "Consumption Trends of Foreign Visitors to Japan - Annual Report 2024," the most popular items in drugstores in recent years have gradually shifted from eye drops, fever-reducing patches, steam eye masks, and face masks to limited-edition packaged foods (such as matcha and yuzu flavors) and regional collaboration products.

Take it back → Experience it locally

Show off your shopping experiences → Show off your photos and food experiences

Drugstore Shopping Spree → Ginza Brands, Local Handmade Products, Limited-Time Experiences

Our generation experienced the takeoff of Chinese consumption, the liberalization of travel to Japan, the exchange rate going from high to low (to the "bottom") , and the information asymmetry on social media. Now, we've gone from being skeptical to fans of Japanese goods, and then back to being indifferent.

And we're getting older; after 35, we become more cautious about shopping. We won't buy anything we don't need or whose effects are unclear.

Do the younger generation stock up on cosmetics at drugstores? No, what they "stock up on" is anime merchandise. My classmate from Waseda University, born in the mid-90s, went back to Japan only to "eat Hiya" (fans or gamers buy Japanese figurines, posters, badges, limited edition merchandise, etc.) , and while stocking up, he admitted that for good quality and low prices, China is still the best choice. Drugstores are not the main purpose of the younger generation's trips.

When people have money, they develop material desires, which always need to be satisfied. But with more choices, people no longer need to be fixated on a single channel or method.

Based on my observations over the past few years in Japan, the pace of change in Chinese commerce is like a day in the sky, while in Japan it's like a year on earth. As Chinese products innovate faster and consumers become more aware of new concepts, and as Japanese tourism offerings become more sophisticated, the relationship between the two will naturally move towards a more balanced state.

It's not "fanatical", not "superstitious", and not "harvesting", but rather a system where everyone gets what they need, pays according to their needs, and votes with their feet.

This is what constitutes a mature era of cross-border consumption.